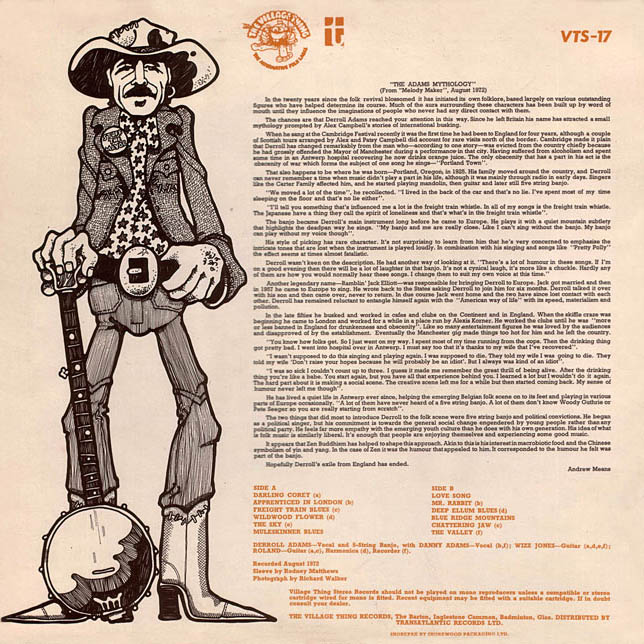

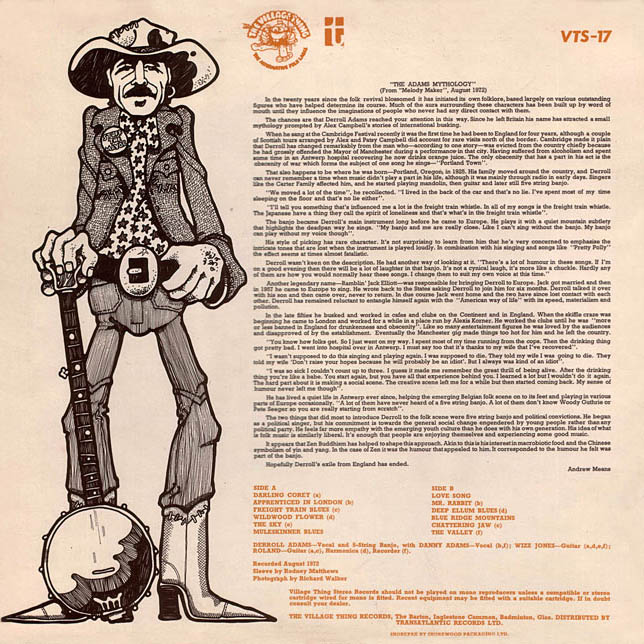

"THE ADAMS MYTHOLOGY"

(From "Melody Maker", August 1972)

In the twenty years since the folk revival blossomed it has initiated its own folklore, based largely on various outstanding figures who have helped determine its course. Much of the aura surrounding these characters has been built up by word of mouth until they influence the imaginations of people who never had any direct contact with them.

The chances are that Derroll Adams reached your attention in this way. Since he left Britain his name has attracted a small mythology prompted by Alex Campbell's stories of international busking.

When he sang at the Cambridge Festival recently it was the first time he had been to England for four years, although a couple of Scottish tours arranged by Alex and Patsy Campbell did account for rare visits north of the border. Cambridge made it plain that Derroll has changed remarkably from the man who—according to one story—was evicted from the country chiefly because he had grossly offended the Mayor of Manchester during a performance-in that city. Having suffered from alcoholism and spent some time in an Antwerp hospital recovering he now drinks orange juice. The only obscenity that has a part in his act is the obscenity of war which forms the subject of one song he sings—"Portland Town".

That also happens to be where he was born—Portland, Oregon; in 1928. His family moved around the country, and Derroll as never remember a time when music didn't play a part in his life, although it was mainly through radio in early days. Singers like the Carter Family affected him, and he started playing mandolin, then guitar and later still five string banjo.

"We moved a lot of the time", he recollected. "I lived in the back of the car and that's no lie. I've spent most of my time sleeping on the floor and that's no lie either".

“I’Il tell you something that's influenced me a lot is the freight train whistle. In all of my songs is the freight train whistle. The Japanese have a thing they call the spirit of loneliness and that's what's in the freight train whistle".

The banjo became Derroll's main instrument long before he came to Europe. He plays it with a quiet mountain subtlety that highlights the deadpan way he sings. "My banjo and me are really close. Like I can't sing without the banjo. My banjo as play without my voice though".

His style of picking has rare character. It's not surprising to learn from him that he's very concerned to emphasise the intricate tones that are lost when the instrument is played loudly. In combination with his singing and songs like "Pretty Polly" the effect seems at times almost fatalistic.

Derroll wasn't keen on the description. He had another way of looking at it. "There's a lot of humour in these songs. If I'm on a good evening then there will be a lot of laughter in that banjo. It's not a cynical laugh, it's more like a chuckle. Hardly any of them are how you would normally hear these songs. I change them to suit my own voice at this time."

Another legendary name—Ramblin' Jack Elliott—was responsible for bringing Derroll to Europe. Jack got married and then in 1987 he came to Europe to sing. He wrote back to the States asking Derroll to join him for six months. Derroll talked it over with his son and then came over, never to return. In due course Jack went home and the two have since lost contact with each other. Derroll has remained reluctant to entangle himself again with the "American way of life" with its speed, materialism and pollution.

In the late fifties he busked and worked in cafes and clubs on the Continent and in England. When the skiffle craze was beginning he came to London and worked for a while in a place run by Alexis Korner. He worked the clubs until he was "more or less banned in England for drunkenness and obscenity". Like so many 'entertainment figures he was loved by the audiences clad disapproved of by the establishment. Eventually the Manchester gig made things too hot for him and he left the country.

"You know how folks get. So I just went on my way. I spent most of my time running from the cops. Then the drinking thing got pretty bad. I went into hospital over in Antwerp. I must say too that it's thanks to my wife that I've recovered".

"I wasn't supposed to do this singing and playing again. I was supposed to die. They told my wife I was going to die. They told my wife 'Don't raise your hopes because he will probably be an idiot'. But I always was kind of an idiot".

"I was so sick I couldn't count up to three. I guess it made me remember the great thrill of being alive. After the drinking thing you're like a babe. You start again, but you have all that experience behind you. I learned a lot but I wouldn't do it again. The hard part about it is making a social scene. The creative scene left me for a while but then started coming back. My sense of humour never left me though".

He has lived a quiet life in Antwerp ever since, helping the emerging Belgian folk scene on to its feet and playing in various parts of Europe occasionally. "A lot of them have never heard of a five string banjo. A lot of them don't know Woody Guthrie or Pete Seeger so you are really starting from scratch".

The two things that did most to introduce Derroll to the folk scene were five string banjo and political convictions. He began as a political singer, but his commitment is towards the general social change engendered by young people rather than any political party. He feels tar more empathy with the emerging youth culture than he does with his own generation. His idea of what is folk music is similarly liberal. It's enough that people are enjoying themselves and experiencing some good music.

It appears that Zen Buddhism has helped to shape this approach. Akin to this is his interest in macrobiotic food and the Chinese symbolism of yin and yang. In the case of Zen it was the humour that appealed to him. It corresponded to the humour he felt was part of the banjo.

Hopefully Derroll's exile from England has ended.

Andrew Means